Extreme operating excellence in life

And how kicking ourselves into mental overdrive gets us there

The first taste of deep care

I was a pretty great student through most of grade school - I cared deeply about my classes and gave the maximum effort in extracurriculars and sports while remaining numb to the setbacks (like never making the volleyball team in high school).

In my senior year of high school, I reallocated a lot of my time from conventional school-related activities towards learning about startups and tech, building small projects and meeting people in the space. Through the help of a student program, I was building a foundational passion for wanting to work on tech companies. The peak of those experiences — and also the trough of the mental commitment I was giving to school — was a high school internship at a big bank working on machine learning projects in the summer after my senior year of high school. I felt mentally zen and enjoyed putting in as much effort as I could. Unlike school, it felt real and the right thing to chase.

That time represented a local maxima in my life for having deep care and dedication to something—to the level that I would be thinking about it in the shower, on commutes, and before going to bed.

Because in the four years succeeding that time, in university when I studied software engineering, I progressed to the other end of the spectrum and became a mediocre student, losing the level of care and attention for the ‘main thing’.

An unintentional shift to little purpose

While in university I always felt uncomfortable with the way I carried myself, from a professional and academic perspective. At first, I thought I had recklessly lost my work ethic, and refused to believe I had a foundational disinterest in the things I had chosen to study. Switching wasn’t an option, because I thought it would represent “losing” the mental battle with myself — that my procrastination and laziness were forcing me to take an easier path, and I wasn’t okay to let myself stoop that low.

I became an observer of life passing by because I started operating with less-than-great principles and didn’t feel the motivation to try. I felt like I had an empty purpose and also didn’t realize it was in my power to change that. It was a fun time: hanging out and living with my friends, going out and partying; but it was just that.

Over time, I found other outlets where I naturally was spending a lot of my time, giving deep care to my efforts and thinking about it a lot; closely resembling the operating principles from high school.

I started exploring VC, interned at a high-growth fintech startup, and started passion reading about economics and law. Things of true interest. Though it didn’t feel like I had found the right outlet, because engineering courses were still my “day job”.

In hindsight, I realize I drifted away from striving to practice extreme excellence in how I carried myself through life and on interactions with the things I had to spend my time on — purely out of disinterest, and a lack of internal motivation.

Life until that point granted a default outlet and purpose (school) and I loved trying to be great at the ‘main thing’; the pursuit of excellence felt intrinsically good. I didn’t see all the time I had to put in as ‘effort’.

But I also received the premature blessing of noticing the ‘real’ things sooner and had yet to realize it was up to me to land on a new outlet to practice the chase for being great at something.

Rediscovering outlets in cycling

When COVID first hit and everything shut down in early 2020, I started road cycling a lot. I had impulsively purchased once at Walmart before heading to university (and luckily avoided the crazy backlog of bike orders), and in an effort to fight boredom, I took up the hobby. It quickly engulfed my time completely — as a way to stay fit, explore rural landscapes in my city, give me time to listen to podcasts, and later become my new outlet.

Over the 2020 season, my average speed and power increased from ~17 km/hr and ~60 W over 5 km, to ~34 km/hr and ~180 W over 50 km. I became obsessed with tracking every minor change in my cycling performance, nerding out over the numbers, and hyper-analyzing how I could improve in single-digit percentage points: how my arm could be better positioned on the bar, the resting spot of my foot on the pedals—the most tedious of details.

It was the first time in a few years, since the end of high school, that I found an outlet where I felt motivated to pursue extreme operating excellence. Through cycling and other extracurriculars, I realized it was the zen state that facilitated a mindset of chasing being the best in a craft, that I loved. And as a downstream effect, it drew on to how I subconsciously carried my life.

For better or for worse, the state of wanting to be excellent grows only in areas of personal intellectual curiosity—it happened that software engineering classes don’t manifest that for me, and I never want to make the mistake of dedicating myself to work that doesn’t make me want to relentlessly chase a state of irregularly high performance.

For what it was worth, I was lucky to intern with a great team after my junior year of university, and while pursuing excellence there, I learned more than what school had tried to teach for four years.

A quote

A by-product of an interest in cycling was starting to follow the Tour de France — someone who appreciates excellence in a field loves watching it, and so I naturally became interested in the sport.

Greg Lemond’s career caught my eye: he is a 3-time Tour winner (the first and only American to do so, so far), he returned from a hunting accident that lost 65% of his blood volume and brought him 20 minutes away from death to another Tour win. Most notably, I admire his saying:

It never gets easier, you just get faster.

That principle touches more aspects of high performance in life than what it initially lets on.

The “physics” of it

In the first season of cycling, when I became more intuitively comfortable and intrinsically enjoyed it, I also started running and swimming more (I had a phase when I thought qualifying for the Olympics as a triathlete was ~easy~). Running didn’t come as naturally as biking for me: my muscles hurt and I’d hear the voice in my brain telling me to slow down or take a break.

My second cycling season was when I first started hearing that same voice. On windy or rainy days, and on routes with steep inclines, the mental resistance to keep going is high and it’s pretty relieving to stop—but if you do, you’ve lost. You have to lock in and fight the mental urge, to a point of extreme where you become numb to the voice in your head, and the results after that blow past the competition.

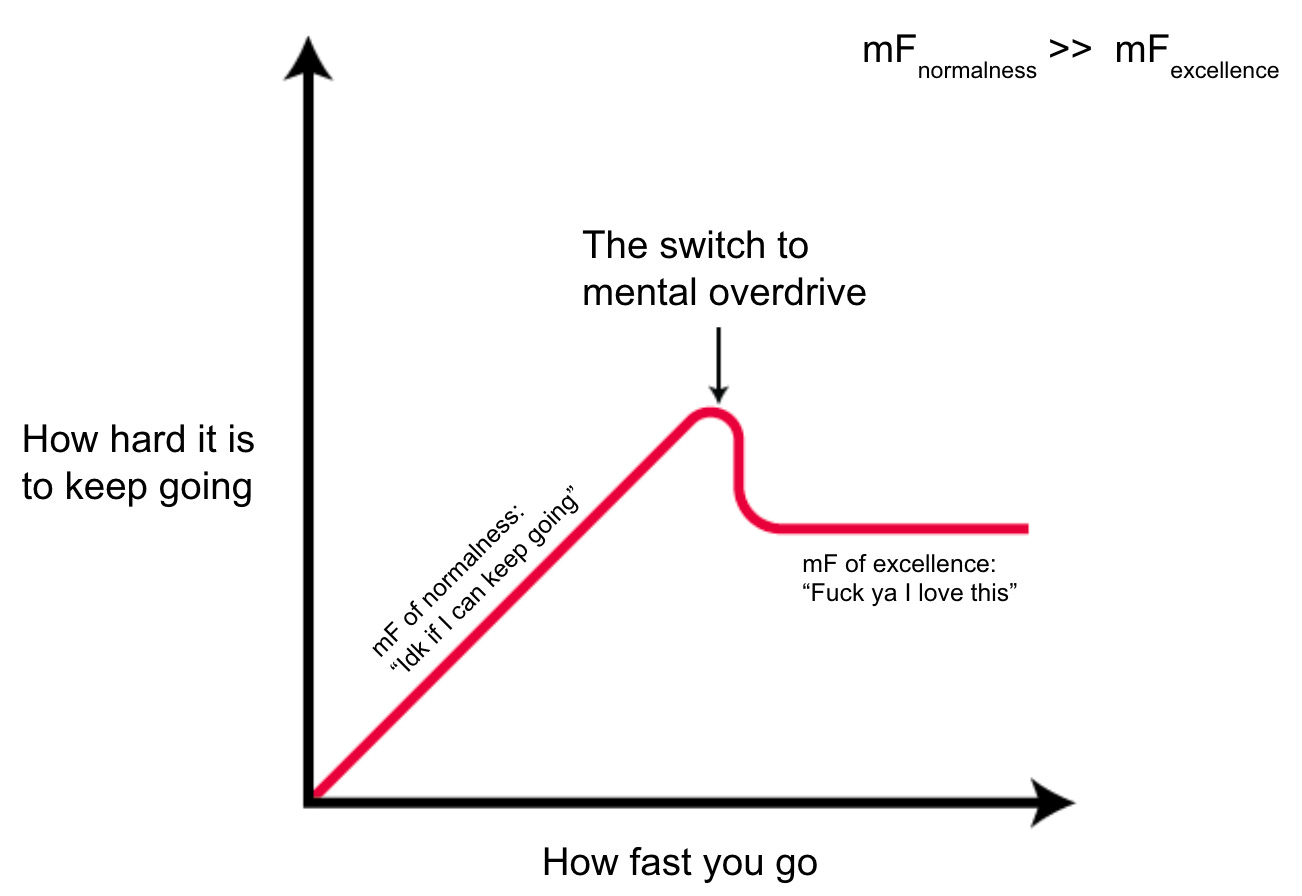

Newton’s first law has a good way of helping to frame this, in analogizing with static/kinetic friction:

Our force of effort rises, and proportionally so does how hard it is to keep adding an incremental unit of effort. Let’s assume our effort is efficient (ie. well thought out, intentional), and so we also happen to get proportionally “faster”.

This keeps increasing until it reaches a point of mental friction (mF) of normalness. Most people usually quit here - it’s their perceived limit for pushing themselves.

But those who are truly in the pursuit of greatness switch into mental overdrive and keep pushing; they become numb to the mental resistance and achieve a state of pure performance dedication.

The mental friction of excellence against every incremental unit of effort past this point may still exist, but it’s nowhere close to the mental friction of normalness; just like static and kinetic friction dynamics.

All this is to say, to kick ourselves into mental overdrive in pursuit of excellence in whatever our craft is, we have to first be able to recognize when we quit just because it’s getting tough—because chances are, it’s the perceived limits of our ability that we confuse with our actual limits.

When we lock in and push ourselves further, we end up going “faster” than most other people (because they quit, as we would if we listened to the voice in our head).

Then at a certain point, past the switch into overdrive, we are in a position to truly reach the highest level of performance in the things we do, and have a chance at becoming great.

It’s why Steph Curry is the three-pointer lead of all time: no matter the day, the workout routine does not gets skipped. It doesn’t matter if last night was a late night, if we performed extra well the game before, or anything else.

It’s why Elon Musk slept on the Tesla factory floor when the Model 3 was experiencing severe production difficulties, delays and costs.

At that level of operating, the pain is hidden from us in the focus on achieving perfection. But it only happens on a thing we truly care about, and requires us to mentally buckle down and let our conscience learn what we’re actually capable of.

Have I ever experienced this professionally? Not yet — so that’s the only disclaimer here. These are simply the inferences from spending two years cycling in a period where I was—without realizing at the moment—desperately looking for an outlet I’d be interested in pursuing excellence.

The point

I was having a conversation with a close friend who recently joked that I didn’t have a great work ethic (I don’t blame them for saying that—they’ve only seen me in the outlet of school). It’s something I couldn’t stop thinking about, and what led me to write this. I realized that behaviour is a function of the environment that I let influence my mindset — it’s what happens if I don’t actively seek something that lets me manifest deep care and inspires a pursuit for excellence.

One of the purposes of life (without sounding too grandiose) should be to explore crafts to exercise the highest level of performance until we come across an outlet we truly resonate with. To chase obsession.

When you constantly brush and cross the border of mental overdrive between normalness and excellence, and don’t quit, you’ll feel the zen state that the highest performance people seem to feel in their crafts; and it’s only fuel to help you push through.

That feeling of mental overdrive will never not feel hard, but you’ll always keep getting closer to true excellence—even if that’s a goalpost you never actually reach.

It doesn’t get easier, you just go faster.

In the relentless pursuit of extreme operating excellence in one’s craft and life, it’s mostly an internal battle of recognizing when the gap between you, and the level you strive to be at, starts growing.

If the measure for the pursuit of greatness is that it never feels like it gets easier, you’ll know you’re not going as hard as you should because you’ll find yourself not getting faster.

Thanks for reading. Say hi if you’d like!