Intentional thoughts on tech + startups

The shapes and themes to help decide where to spend time, and why more people should think of them more

I think a lot about technology company-building: startups, and how they act as “vehicles” to sustainably deliver a solution to complex problems at scale using tech.

I’ve been deeply curious about founding stories throughout my time in university, and enjoy tinkering with ideas for companies that the world still needs, to the point where I see myself either founding a company or joining an early-stage team in the future.

This train of thought has been so habitual that it represents a subconscious part of my daily thinking appetite and is the focus of lots of intellectual sparring sessions with friends.

Sometimes I’ll notice a non-customer-friendly pattern at a restaurant, and my mind runs on what I’d change as the owner. Other times I come across unfair terms and conditions of a product I use, hate seeing how it could trick people, and that ‘falling in hate’ inspires spending the next week thinking of a better way.

Shapes

Though I’ve had few actual building experiences, I think I’ve done a pretty good job in retaining the earned knowledge through the ones I have had: building a strong intuition in the process (as much as one can have for only having done internships).

Now as I actively think of where I want to spend my time after graduating—whether it be joining something early-stage, the companies I’d want to invest in if I went into VC, or debate starting a company—I have structured thoughts on the characteristics of the thing I pick to commit time to.

Instead of focusing on a sector, domain or demographic to service, I’m thinking more about shapes and themes of problems for an organization or team to work on.

The point of this terminology is to emphasize that often characteristics of interesting opportunities transcend specific lines of business, industries and business model practices—and sometimes touch on elements of all three.

Pulling forward second-time founder lessons

This lack of intentionality usually motivates a lot of people to just start, sometimes into pivots and companies that become successful. Though it feels like I have a clearer head on this, I’ve also spoiled myself through my sustained interest in startups, which ends up raising my bar in mission assessment.

This track of intentionality is something more people should share; I haven’t mastered these ideas or built ultra-strong convictions, but I think having zero progress in understanding a fundamental “why” and preference on a focus area is the exact factor creating the 500th niche B2B SaaS company that drives no meaning to the world.

Why do founders have to wait until their second company to realize they should hold their time in high regard, and only qualify ideas that are truly significant in a positive way to work on? Imagine the founder-hours we waste on mediocrely interesting and marginally-impactful startups, and the loss when great potential founders don’t build a second company when said ventures fail.

Apoorva Mehta from Instacart talks about having this high bar on working on meaningful things he would also enjoy, and it’s a pretty simple thought that surprisingly is missed by many first-time founders I observe jumping into starting a company.

I’d bet more people would arrive at the conclusion to have the utmost highest bar in the quality of things they spend their time on if they were intentional about understanding their “why” for starting a company.

A running collection of my own

This post is more of a self-reflection via writing; I’ve distilled below some specific shapes and themes of problems I’d want to work on to better hunt for a mission I want to commit my time to for the foreseeable future (or at least one where I can pick someone to convince to bring me on board):

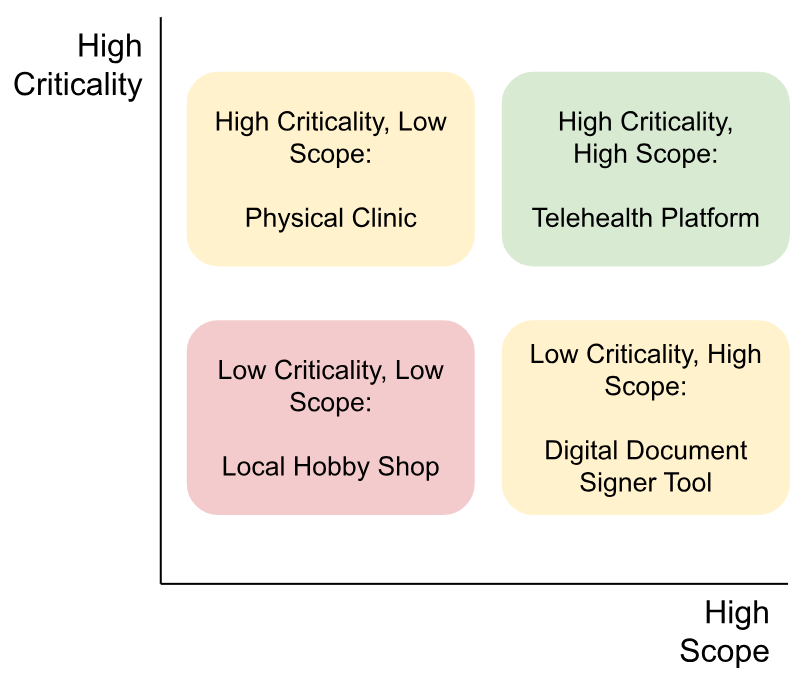

Problems with a high criticality to life and human prosperity, and also ideas that can have high scope without proportional friction to scale.

Imagine Doctors as a job at one end of the criticality spectrum, and large-cap enterprise SaaS salespeople (sorry 😅) at the other. One is objectively helping human life prosper through their work.

That Doctor can only deal with one patient at a time though, so while their work is highly critical, it’s not scalable enough.

Taking a first principles approach, we now want to look for proxy signals that represent opportunities that are both high in scope and high in criticality (because these obvious aren’t labelled as “worth it” or not in the wild for us):

High Scopes

Businesses with non-first order effects. I’ve found that the extent of a business’s indirectness to the consumer—in that there are multiple orders of players before the final product beneficiary receives the experiences—correlates with its impact scope. The further ‘up chain’ a business is, the wider the breadth of people who use the product.

Usually, this manifests as API businesses: Stripe builds a product designed to partially provide a superior buyer experience when people try to pay for something online. In the most extreme case, the product is first delivered to a platform business, which is enabled to provide a service to another business/individual operator, who serves the end user (think Uber, Instacart, Doordash, Amazon, Shopify, etc).

Infrastructure/platform technologies businesses are other examples of “non-first-order-ness”: OpenAI’s ChatGPT is a product that enables certain functions, that as a result enable another company to do something easier/faster/cheaper for an end consumer. The shift to mobile computing is another example: it enabled a cohort of ideas that couldn’t previously solve certain problems.

Flexport’s ability to reduce poverty rates via global shipping technology is another great example of this: Better tech → more freight forwarding efficiency → lower tariff rate + higher trade volume → lower poverty rates

It’s important to note that each “order” in the chain needs to provide some value or do something of use with the product they're being handed from the provider, to not just be a middleman and sink value. Ex: Shopify builds e-commerce software using the payments APIs Stripe hands them, which allows merchants to sell things online to people like us.

Problem spaces that need straightening of unaligned economic incentives. The very fact of a market or customer demographic injustice existing indicates that 1) the people it serves need the thing, enough to look past unfair product tactics, and 2) that strong demand mitigates any market risk for a new idea that ‘rights’ the wrong of the existing thing. There usually is some third-degree risk in the market (not relating to the direct consumers or execution potential) that discourages competitors: this could be regulation, the economics of scale of incumbents, or purely a tediousness in barrier to entry.

Early D2C companies exploited this angle: Warby Parker taking on Luxottica, Harry’s and Dollar Shave Club taking on P&G, jet.com taking on the fulfillment inefficiencies of Walmart, etc.

Consumer fintechs building condensed products that remove unnecessary fees and friction

It’s important to note that sometimes these unaligned incentive structures aren’t intentional, and could just be the product of a changing market or new technologies, and an incumbent who hasn’t caught up yet.

Geographically bound disadvantages in problem areas that should be agnostic. This is usually the consequence of a highly-physical industry not realizing the benefits of digitization quickly enough. When present for long enough, it starts to uncover pressing inefficiencies in the way things are done.

The gravity equation shouldn’t exist in digital “trade” (of value, goods, knowledge, otherwise): where trade strength is inversely proportional to the distance between two parties.

Blockchain technology, most notably Bitcoin and Ethereum, enables this for the transfer of durable value; Internet networking protocols enable this for content and information movement. More mildly, Stripe acts as an on-ramp/off-ramp intermediary for global value transfer, abstracting away the geographically-sensitive complexity

“The human body does not change how it behaves when it crosses state lines.”

High Criticality

Complexity is often present in problem spaces that drive drastic suffering to a user’s experience. And this is often correlated with highly “physical” areas.

Usually, this revolves around non-market and -execution risks: government and regulatory, oligopolistic pressures, availability of a specific technology, etc.

The more physical a problem area is, and therefore likely more complex, the more critical and positive a solution in the area will be to the lives of those who experience said problem.

It’s when we combine these highly physical problems with solutions that benefit from the scale characteristics of software can address them really effectively.

Ambrook helping improve farms, Flexport reducing supply chain inefficiencies, Uber connecting drivers with cars to people who need a ride

Industries that have non-technical barriers to build are a proxy of physicalness/complexity (like the above point).

Beyond market/execution risk: policy, market comfortability + adoption slowness, oligopolistic or current best-practices market pressure

This is often the reason climate, government tech, space and similar ‘on the edge’ domains are unsexy for founders to work in.

Success in these areas usually requires a much larger timeline than a quick social media app virality cycle and is often tedious to work in. They feature problems that can’t entirely be solved by a skillset in technology and business.

Ideas that cut the Gordian knot (the idea of reducing complexity in a challenge by circumnavigating the main source of the challenge): sort of a triple agent when it comes to innovation thinking.

Founding theses that try to take a step back from advanced tech-based solutions and do something simple/conventional, but with a highly unique delivery/approach; like synthetic hydrocarbons instead of battery electric vehicles.

It may not work, and the crowd may be right this time, but the risk of going against the crowd to see if there’s a better way is always admirable even when said crowd is already going against an even more conventional crowd

Founders with “larger than self” theses for life, and how company building is their method to work towards their thesis

Evidence of exacting craftsmanship: caring about the nitty gritty, and how it’s obvious in the product or experience

10x > 10%: Orders of improvement, instead of marginal

These are also often missions with the natural ability to attract crazy talent (top 1% in ambitiousness)

Most people, when asked if they’d work for such a company and mission (regardless of role), would answer “hell yes”

These are often also noble ideas: where deep care is attributed to the prosperity of one or many demographics of humans

A ripple in the market

Chris Paik talks about the idea of the most explosive enterprise value creation happening only by companies founded at the onset of a major market dislocation that enables a key part of the company that previously wasn’t possible.

The most valuable 2010s tech companies rode the wave of mobile and 3G computing: the ability for certain things to be done on a connected phone allowed the possibility for the gig-economy companies; Snapchat and TikTok relied on network bandwidth that allowed for feasible video data transfer; OpenAI needed the advent of scaled machine learning models and low hardware compute cost to enable consumerized use of AI.

Most of these are captured technology-driven market dislocations, that present some market risk because there is a “new” thing that definitionally couldn’t exist before. On one hand, this can justify why rapid growth can happen, but on the other hand, it suggests anything that isn’t driven by a direct technology-driven market dislocation may not be a great venture-backable and value-creating business.

I’d like to suggest an amendment to the definition of a market dislocation:

So far, we’ve seen tech-driven reasons for a market dislocation to exist. But there are also significant examples of startups that created extreme value while riding on a technology that wasn’t anything new.

The dislocation existed as a competitor, regulatory and pure market element.

Tackling a customer segment by using a more sensical GTM approach than the one incumbents employ (which they probably do because it asymmetrically benefits them anyway). Anduril countered the existing cost-plus contracting practice for government defence contracts. Hardware and robotics were nothing new at the time.

Shrinking the size of a market—because the status quo players don’t charge responsibly causing the the current market size to be unnecessarily large—via company building with better practices to capture a higher share of the smaller landscape, like Ro in US healthcare. At Ro’s beginning, the product was purely software, though regulations of physician credentialing probably were both the barrier to growth and as Ro made progress, their moat against competitors.

Affirm’s success entirely rests on a business model innovation: the combination of revolving lines of credit like loans, but issuable at point of sale like credit cards. Beyond making more sense for certain purchases from a product experience standpoint, it also eroded levers that banks would use to commit product injustices, taking advantage of users by charging exorbitantly.

Airbnb (and Uber, as early gig-economy companies) ushered in a shift in consumer behaviour that enabled their businesses to grow. These companies identified a dislocation in the market that wasn’t even really a mismatch until they came along. I think it’s completely normal to rent a stranger’s apartment halfway across the world now, but that was insane 10 years ago. And beyond the distribution of the internet, there wasn’t any crazy new technology used to enable explosive value creation.

Some caveats though:

There could be serious impediments to scaling a company by taking advantage of a non-technology-based market dislocation, like the need for significant capital to start, or size and economies of scale. It may also be the case that potential competitors don’t succeed because it requires convincing a large group of consumers of a fundamental shift in consumer behaviour that is considered weird.

As access to building with advanced technology gets democratized, it’ll be more than just a technology-based market dislocation as the only plausible market “ripple” to exploit and build a great company out of.

While there’ll definitely be exceptions to all of these rules—companies that fit the shape but aren’t high in scope or criticality—I think trying to check off as many as possible is the right way of refining and filtering for truly meaningful places to spend your time helping build or directly start.

High-level personal themes

Gearing these shapes in the context of a specific theme can also help narrow the initial exploration process, as well as give a clearer understanding of the domain areas where you want to try and manifest these shapes.

I want to be able to answer this question 30 years from now really effectively:

“Is there a high-level theme or principle you’re following in making your career decisions, that together achieve a macro goal you find really meaningful to your life?”

In the context of technology companies, this is usually around the thematic mission you want to align all your work with. Doesn’t have to be one, but I’d be surprised if all the seemingly different professional adventures don’t share a higher-level principle.

My answer for this right now: I can see myself dedicating all the work in my life to helping build software that materially improves economic prosperity at scale. That conclusion isn’t the product of crazy self-reflection; but rather an assessment of the fundamental reasons why I was interested in the things I was interested in.

With this, I can justify current and past intellectual explorations like fintech, emerging markets and international development, global trade systems, verticalized primary care, industrial biotechnology, etc.

The point

Primarily, this is a method to further solidify (or potentially disprove) my own thoughts; all in the hopes of hearing feedback or disagreements on anything I’ve discussed from strangers!

I’m going through a phase of being uncertain of the areas I want to spend time working on next, now that I’ve graduated from university. I want to be adjacent to startups, but don’t have enough conviction in my own ideas to commit, and have also only recognized a few places that I could find meaningful to spend my time at.

I want to approach that ongoing debate with a set of principled thoughts and ideas that hold my decisions to a high bar. While I *want* to be a founder, my goal is to prevent that for as long as possible by finding missions that align with the themes most interesting to me and meet the minimum shapes of what its respective opportunity looks like. And if/when I fail at preventing being a founder—because I’ve found an area that *needs* me to do something on my own—I’ve won anyway.

It’d be cool for the world to have more principled builders.

Thx for reading. Say hi if you’d like!